Educational content on VJHemOnc is intended for healthcare professionals only. By visiting this website and accessing this information you confirm that you are a healthcare professional.

In this case study on newly diagnosed AML, learn more about:

✓ Approaching diagnosis and disease classification

✓ Treatment options for newly diagnosed AML

✓ The importance of recurrent genetic alterations when making treatment decisions

Case presentation: A 73-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with a fever and fatigue. His initial laboratory studies show an elevated white blood cell count with anemia and thrombocytopenia (Table 1) raising suspicion for possible acute leukemia.

- A bone marrow aspiration (Fig 1A) and biopsy (Fig 1B) showed markedly increased blasts. By immunohistochemistry, blasts were positive for cytoplasmic NPM1 (mutant pattern, Fig 1C).

- Cytogenetic studies performed on the bone marrow aspirate showed a diploid male karyotype (46, XY[20]).

- PCR followed by capillary electrophoresis showed the presence of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutation.

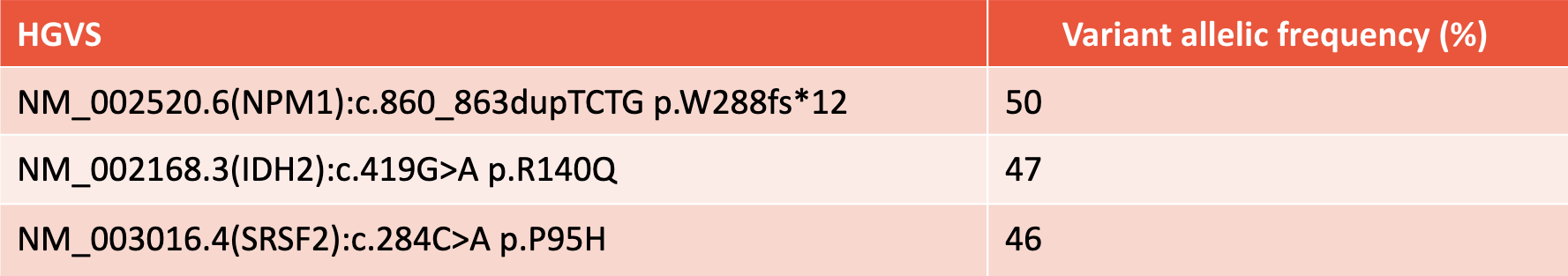

- Next-generation sequencing showed the following pathogenic mutations:

Figure 1

Table 1

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

Alright, so hello everybody. My name is Sanam Loghavi. I’m a hematopathologist at MD Anderson Cancer Center, and I’m joined here today by my colleague Dr. Naval Daver, who is a professor of leukemia, also at MD Anderson Cancer Center. We’d like to discuss a case of AML with you, acute myeloid leukemia.

I’m going to present the pathology of this newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia to Dr. Daver, and we’re going to discuss treatment options for this patient in the context of their molecular findings.

So Dr. Daver, this is a 73-year-old man who presents with newly diagnosed leukemia and elevated white blood cell count. We have done phenotyping on the leukemia on the bone marrow aspirate and determined it to be an acute myeloid leukemia. Molecular studies show an NPM1 mutation, a FLT3 internal tandem or ITD mutation, and also the presence of an SRSF2 mutation.

In this context, we want to talk about risk stratification for newly diagnosed AML. What are the molecular findings that go into risk stratification? And sorry, I forgot to mention this patient has a diploid carrier type. And also, how do you decide on what FLT3 inhibitor to use and how do you decide on maintenance therapy for this patient?

So, what are the frontline options available for a patient of over 70, 65 years old with this type of AML?

Dr. Naval Daver:

Thank you very much, Dr. Loghavi, for having me. It’s great to be here and looking forward to this discussion. I think one of the areas in acute myeloid leukemia where there has been the most progress has been both identification of molecular mutations as well as their prognostic and predictive value. And FLT3 probably is the one with the most data aggregated, both from prognostic point of view as well as from using it in a therapy setting.

So for such a patient, let’s say an older patient above 65/70 with a newly diagnosed FLT3 mutation, NPM1 mutation, I think the first key point is that we want to wait for mutational testing. There’s a lot of debate about whether you need mutation testing in older patients based on the use of HMA-venetoclax. Although when we start looking at the details of the VIALE-A outcomes, we do identify certain subsets that do not do as well.

This includes TP53, FLT3, RAS mutation, monocytic groups, and especially for FLT3, we think that incorporating a FLT3 inhibitor may actually further improve the outcome. So our practice at MD Anderson has been to check mutational testing for older patients. FLT3 may get different treatment options. IDH, there are treatment options for that. And for TP53, we have a number of trials.

Now maybe in the near future for MLL rearranged NPM1, we have other combinations of HMA-VEN plus menin inhibitors. So I think that debate of whether we need to wait for molecular results in older patients, I think to us at least at MD Anderson, that is not a debate. We do wait for it. Of course, because of your help and your molecular colleagues, we have the luxury of getting these results in five to seven days, and many academic centers in the US are starting to have similar timelines. So, if we can get it that quickly, I would wait.

So that being said, we waited, we got the results for this patient, diploid cytogenetics, FLT3, NPM1, SRSF2. So this is not uncommon. About 15 to 20% of older AML will have a FLT3-ITD mutation. It’s a little less frequent in older compared to younger, where it may be up to 30-35%, but still probably one of the most common mutations.

The frontline treatment, when you look at the traditional treatment, it has historically been HMA-based for older unfit patients. We avoid the use of intensive chemo in patients above 70 and even above 65 because of the very high induction-related mortality that has been shown multiple different times in multiple different studies with anthracycline-cytarabine.

So one could then consider use of HMA-VEN saying that maybe this patient may not be a great candidate for induction chemotherapy. And in general, maybe five years ago, that is what we would’ve thought when we were doing the HMA-VEN studies. But as I said, now, with the recent molecular analysis of the VIALE-A study, we have seen that FLT3-ITD-mutated, even though they have a high CR/CRi rate, about 70%, very similar to the non-FLT3-mutated patients with HMA-VEN,

the median survival was actually only around 11 months, not 15 or 20 months, as we see with non-FLT3-mutated. It actually was a little bit better, but not too much better than HMA alone. So we started seeing these data. First we published it, then DiNardo and group published it on the larger VIALE-A analysis. So in the last three, four years, our effort has been how can we improve this outcome in all subsets beyond HMA-VEN, but especially in FLT3?

So with that, we started adding FLT3 inhibitors, and there are many effective FLT3 inhibitors now US FDA approved in different settings. So these include gilteritinib, which is approved in the relapse/refractory setting, this is a type one FLT3 inhibitor so it has the advantage of targeting both ITD and TKD. Quizartinib was very recently approved, this is in the frontline setting with intensive chemo for younger patients. This drug is a type two FLT3 inhibitor. It’s a very potent FLT3 inhibitor. Pre-clinically, actually, it was the most potent, but it does not hit the TKD so we can see escape through TKD. And then midostaurin, which is kind of a first-generation older FLT3 inhibitor but a reasonable drug, was actually the one that was approved a few years ago, and has been used in frontline intensive chemo setting.

So when we started evaluating how to further improve on HMA-VEN, we incorporated gilteritinib and quizartinib, in two parallel studies, added to HMA-VEN. The first goal of these studies was really to identify how to deliver safely a third drug added to a backbone of a doublet. So we started very cautiously with lower doses and only 14 days of venetoclax with quizartinib/gilteritinib, adding lower doses of those drugs.

We actually found that if we gave only 14 days of VEN, along with 14 days of the FLT3 inhibitor, this was actually quite tolerable. In different cohorts when we tried to give 21/28 days of VEN, in fact, the myelosuppression added up very quickly and we started seeing prolonged neutropenia and cytopenia. But with 14 days of VEN, 14 days of gilteritinib, or 14 days of quizartinib added to HMA backbone, was actually very, very tolerable.

This study was led by Dr. Short, the AZA-VEN-GILT study should be published very soon, it’s accepted in the JCO. And then we have a parallel DAC-VEN-QUIZ that Dr. Yilmaz in our group has been leading, and we presented that data at the ASH meeting. What’s amazing is the response rate with both the AZA-VEN-GILT, 30 patients, and the DAC-VEN-QUIZ, about 15 patients, is actually close to 100%.

We’re seeing CR/CRi in almost everybody, and not only that, the true CR rate, full count recovery, ANC platelet recovery, is also 90%. So even when we just look at the response compared to the VIALE-A, the true CR rate in FLT3 was only about 35-40%. Now we’re looking at numbers close to 90%. What’s nice is both the studies are showing the same thing, so this is not just one study or a fluke, we think this is a real effect.

So that is our current approach, is to use HMA-VEN with the FLT3 inhibitor. These are still ongoing trials. Actually, a larger multi-center trial, led by Dr. Altman and myself now in about 30 centers in the US, has opened with AZA-VEN-GILT called The VICEROY Study. We hope this will serve as a confirmatory study to the studies that Dr. Short and Yilmaz are doing.

I think in the future, in fact, many centers have already started to do this, I think HMA-VEN-FLT3 triplet will be the way to go. The survival data is also looking quite good. We have about a one and a half year survival data looking at almost 70-75% compared to HMA-VEN, which is about 30% at one and a half years for this population. So I think there’s going to be good progress with this approach, but there are still many unanswered questions.

One of these is how long do you need to give treatment? Can you use molecular MRD or flow MRD or both to stop treatment in some patients? Do you give the triplet continuously for many months or do you start with a triplet almost as an induction, achieve a deep molecular remission and then de-escalate to a doublet or even single agent?

So this is kind of the next three to four years where we want to figure out how to optimally give it and then de-escalate it in those who may not need continuation of all three drugs.

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

This is perfect and very encouraging. And actually a perfect segue to my next question about MRD monitoring, so measurable residual disease. So as you know, in the current ELN guidelines, FLT3 is not included as an MRD marker.

However, subsequent to the publication of those guidelines, there’s been unequivocal data showing that the presence of FLT3 MRD does in fact correlate with outcomes. So we hope that we’re going to see them in the next iteration of the ELN guidelines. But right now, clinically and in practice, it is important to monitor both NPM1 and FLT3 in the setting of MRD assessment.

So a couple of things, maybe from the molecular perspective, just to point out that when we talk about molecular MRD, we are referring to highly sensitive tests, right? So this is different from the baseline test that is done to assess the presence or absence of FLT3 or NPM1 mutations. For MRD level, you really want something that achieves maybe 10 to the minus four, 10 to the minus six level optimally. This can be achieved with error-corrected NGS or RT-PCR.

So with that in mind, how often are you monitoring this? How often are you doing FLT3, let’s say, or NPM1 MRD after remission, and how long do you continue to do it?

Dr. Naval Daver:

So I think a couple of points that you brought up are important I think that we want to probably highlight. So one is the changes in the ELN, right, and I think this is kind of not surprising to us, it is surprising sometimes to, I think, those who may not see as much leukemia. But I always say, and actually Dr. [inaudible 00:10:17] has always said this for decades already, is that the prognostic systems are only dependent on the effectiveness of the therapy.

So when you get a good therapy, it actually will completely change the prognostication. We have seen this in ALL, for example, even better than AML. Where Philadelphia-positive ALL only 20 years ago, 22 years ago when I was in medical school residency, we wrote a paper saying it’s a bad group, 25% survival, even pediatrics were not doing well.

Today, 20 years later, we actually consider it not only intermediate, but in fact when I see an ALL patient, I hope they’re Philadelphia-positive because we now have blinatumomab-ponatinib chemotherapy-free treatment firstline in ALL giving us 95% CR rates and good durable survival. So this really changed the whole prognostic approach to ALL.

The same thing I think is happening with FLT3 AML. So FLT3 AML 20 years ago, published by the German, British, and our group, almost at the same time, showed that five-year survival was about 30% in newly diagnosed young patients with FLT3 AML. So it’s clearly adverse, maybe a little better than TP53 and others, but in the adverse group for sure.

So then we started saying, okay, these patients need transplant. This is what we did with Philadelphia-positive ALL. It’s the first big tool you can use. It’s available, it improves outcome, and it did, it brought it to an intermediate group. So then by 2017, ELN FLT3 AML had become intermediate predominantly because of the use of allotransplant in first remission, because of higher use of higher doses of daunorubicin, and also because some centers started using a pirin analog. Each of these had some incremental benefit, but it was still about 45-50% improved from 25-30% five-year survival.

And then with the use of FLT3 inhibitors, even midostaurin, which is not the most ideal potent FLT3 inhibitor, it was a first-generation multi-kinase, FLT3 inhibitor, but even with that, we started seeing that in fact, when you used a FLT3 inhibitor with induction and transplanted patients in CR1, their outcome was actually quite good and these patients no longer started behaving as adverse.

Interestingly, it did not matter what their FLT3 allelic burden was, what their NPM1 commutation status was, the use of FLT3 inhibitor and transplant seemed to bring all the survival curves close to around 50 to 55%, so now, we consider these intermediate.

But I would say, actually, with the use of gilteritinib/quizartinib, which are even better second-generation FLT3 inhibitors, upfront, the use of allotransplant and potentially we use a maintenance post-transplant, sort of now [presents] a total therapy approach for FLT3, I think in the next five years, this group is going to move into a more favorable group.

It may not be as good as core binding and NPM1, but I think it’s going to be better than the diploid non-FLT3 AML. So this is kind of, over 20 years we’re seeing it going from adverse to intermediate to a more favorable.

Now that being said, the big question is, do we need to transplant all these patients? And I think it’s nice that we have this luxury to ask this question because 10 years ago we didn’t care. We just wanted to cure the patients, get survival, we transplanted everybody. But today we’re seeing that with FLT3 inhibitors, with intensive chemo, with the addition of pirin analogs, we’re achieving very high, close to 90% remission rates.

In fact, we’re seeing a lot of these, whether you use flow MRD or, as you said, deep NGS-PCR approaches going to 10 to minus five and six, we’re seeing high negativity rates, up to 50-60% of responders. So then the question is, do we really need a transplant if there’s no detectable disease by two sensitive MRD methodologies? So many people will hypothesize biologically you don’t but of course we need evidence to really change practice.

So there were actually two nice data sets. One was presented by Mark Levis at EHA last year, where they asked the question, let’s say you have a FLT3-mutated patient, you gave them induction with a FLT3 inhibitor, you took them to transplant. Everybody agrees on that. Now what do you do? Are we done? Can we just wait and observe or is there a role for maintenance post-transplant?

This study was called the MORPHO study, Phase III, large randomized study, 400 patients. In fact, really the first large Phase III randomized study post-transplant to be completed in AML and show positive data. Overall, what they showed was there was a improvement in survival with gilteritinib. The p-value was 0.051. I think statistically, even though it didn’t meet it, clinically, we all have seen the data and it looks positive.

But really more than just should you use maintenance or not? What came out of the study, and I think it was really, really important that the authors did this, is that MRD-based use of gilteritinib is really where we saw the most benefits. So when they looked at MRD using a high-sensitivity, FLT3 NGS-PCR approach that can go down in that situation to 10 H to minus six, and they said now, any patient who has MRD detectable immediately pre- or post-transplant and got gilteritinib versus that patient who had a MRD detectable pre- or post-transplant and did not get gilteritinib, there was a big difference then in relapse-free as well as in the overall survival. So I think this is one of the first studies ever in AML, we have had many such studies in ALL, to show that MRD-directed intervention with the use of directed therapy can actually change the outcome for patients.

So because of this, our group, you, the molecular team, we are all trying to get this high-sensitivity molecular testing. We don’t have it routinely yet available, we will hopefully in the near future, this is the situation in many academic centers still in the US. The problem is flow does not bring the same value, so one cannot use flow MRD. I get a lot of emails from community doctors saying, “Oh, I have MRD-negative/-positive, should I use gilteritinib or not?”

The flow is two to three logs lower than the high sensory NGS-PCR, so in that situation, I would probably err on the side of giving gilteritinib, because when you look at the MORPHO data, basically those who are MRD-negative at 10 H to minus six, and those who got gilteritinib being MRD-positive, both have a similar outcome, 75 to 80% survival. So if you cannot discern because you don’t have that 10 H to minus six assay, it’s better to give the drug, it’s a safe drug, and then you get your patient into that 75-80% survival.

But that’s probably one of the big areas where we will start using pre- and post-transplant MRD and then followed every three months to determine which patients should get gilteritinib, how long, et cetera.

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

That’s very helpful, thank you. I would actually say that maybe the opposite scenario to what you described is saying that… because we know that often FLT3 may actually be subclonal, right?

Dr. Naval Daver:

Mm-hmm.

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

So even if you have a flow-positive MRD, if we’re being purists, right? If you have flow-positive MRD and you really don’t know the FLT3 status, that still doesn’t mean that you have the FLT3, residual FLT3 clone. So, I think we definitely need both.

Dr. Naval Daver:

And that’s where this, we just had a rundown yesterday, we were all discussing this, and that’s where this goes on a divergence from ALL, right? With ALL, things are a little bit easier because if you have clonoSEQ, 10 H to minus six, it is definitely ALL and you can treat it. Or if you have Philadelphia-positive at 10 H to minus six, it’s Philadelphia-positive, it is going to be the driver of relapse, 99% will have it.

With FLT3, you’re absolutely correct, that even if you have a flow-positive and a FLT3-negative, you don’t know if a FLT3 inhibitor is going to help. It could be other clones, it could be a relapse coming through other pathways. And we do see actually, in the recent data sets, up to 50 to 60% of patients relapsing after intensive chemo/FLT3/transplant are emerging as FLT3-negative.

So there’s a big clonal switch or a clonal expansion of non-FLT3 clones. So you’re absolutely right, we do need that specific molecular test to make a decision.

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

Maybe this is interesting because now it seems like the pan-RAS inhibitors are the hot topic for everybody. We know from studies that we’ve done together that emergent RAS mutations are mechanisms of resistance in FLT3-mutated AML, actually Philadelphia-positive, right, a BCR-ABL1 can be an emergent mechanism of resistance.

So one of the things that I would highlight maybe as a molecular pathologist is it is incredibly important to retest the patients as they relapse. So we can’t just assume that they’re relapsing with a clone that they had originally before treatment. So that’s very important, because as more targeted therapies become available, obviously we have the luxury of giving the patients better therapy, so it’s important to know what’s driving the disease.

So one other point that, maybe a detail that we had in this case, was the presence of an SRSF2 mutation, combined with an NPM1 and a FLT3, which in the absence of the SRSF2 mutation would render an intermediate-risk AML for this patient and actually still does, right, with current ELN guidelines. But we know that SRSF2 mutation is part of the myelodysplasia-related mutations that in the absence of NPM1 would actually make this person adverse-risk disease.

So how do you deal with scenarios like this? In this patient with an NPM1-FLT3, do you ignore the SRSF2 for the time being, or do you treat it any differently?

Dr. Naval Daver:

So that’s a great question. We do see these SRSF2, U2AF1, some of these RUNX1 others that may co-occur with FLT3 and/or NPM1. So, in general, just because we have very effective targeted therapy for FLT3 and our path is to move to transplant for all of these patients today. Now, this may become more relevant in the future as we use sequential longitudinal high sensory molecular assays and start thinking about whether or not we’re going to transplant a patient, then I think these third or fourth mutations may start coming into play as to say, are we comfortable not transplanting if there’s an SRSF RUNX1? But today I think we still are going to give FLT3 inhibitor. Ideally, we were preferring a second-generation FLT3 inhibitor, we’re going to transplant, and then we’re going to use post-transplant high sensory molecular MRD to decide whether they get maintenance or not.

So I don’t think it changes outcome, and we’ve actually published that it doesn’t seem to affect the prognosis or outcome in that treatment paradigm. Now I think the second thing that we have to think about is though in these patients, is this truly a marker of adverse disease or not?

There’s been a lot of debate because the ELN includes these eight mutations and they call them secondary-like mutations. But they’re also clubbed together with mutations and other factors that are clearly highly adverse, TP53, chromosome 17, complex cytogen inversion. I think many of us feel that yes, these are both adverse, but there’s an adverse, and then there’s a really adverse.

And so for some of these, we see them, it doesn’t change our treatment approach so much. I think in the future, as well, if we have something like NPM1-FLT3 that can be looked at for MRD, it probably won’t change our treatment approach, the presence or absence of SRSF2. But I think this is something that maybe you can talk about because I know you and others are looking at what is the VAF impact? What scenarios do these secondary-like mutations really clinically matter versus when is it noise? So what are your thoughts on that?

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

Absolutely. So this is very important. Thank you for bringing this up. I think just like every other scenario in AML, AML is a clonally heterogeneous disease, and when we think about it, you really have to think about what is driving the disease? What is the driver of this disease?

And one of the things, not because people didn’t think about it, but I think there’s not sufficient data, is if you look at the classification systems and guidelines, really variant allele frequency has not been incorporated in detail, maybe with the exception of the ICC and ELN using 10% for TP53 and SF3B1, but it hasn’t been incorporated.

So with current classification guidelines, let’s say disregard the NPM1 FLT3 scenario, but if someone has a secondary-type mutation and if they have a 10% SRSF2 VAF, they’re considered an AML with myelodysplasia-related changes or myelodysplasia-related mutation. And then if they have an SRSF2 mutation with a 50% variant allele frequency, they’re also considered to be of the same class.

I think there definitely is a difference and we have exciting data that is going to be published hopefully very soon, but there is a difference in VAF. So if you have a clonally dominant MR type mutation, and actually there was a really nice abstract at ASH this year as well, showing similar results, where if you have a clonally dominant MR-type mutation, those patients tend to have an inferior prognosis. But again, as you said, not as bad as the TP53-mutated cases or as the complex karyotype cases, but they tend to do worse.

Whereas if you have a sub-clonal MR-related mutation, then those are not as bad, and the other drivers are the ones that dictate the prognosis of disease.

Dr. Naval Daver:

I mean, I think it’s fascinating that the amount of molecular information, for example, at this ASH is when you looked 10 years ago, it’s like 30-fold, 40-fold more. I think it really shows not just for baseline, not just for prognostication, not just for therapy selection, but this year especially, there was a lot of data on using it for MRD, which I think is finally where AML MRD is coming into the forefront.

We’ve used flow for many years, but I don’t really see the future five, 10 years from now as being flow as the commercial MRD assay being used for multi-center registration studies. There’s just too many hurdles as you know, logistics and shipping and collection, et cetera. So I think the molecular ones, NPM1, FLT3 are probably going to emerge. The problem is that these only cover about 40%/45% of AML.

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

Yeah, that’s what I wanted to say. So flow is probably going to remain for the ones that don’t have a good molecular MRD marker. So the flow cytometrists don’t, don’t go kill yourself just yet.

Dr. Naval Daver:

No, no, I know. I mean, I just think that it’s hard, even with ALL where flow is actually highly definitive, it’s very hard to replicate it in a multi-center registration study.

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

Oh, absolutely.

Dr. Naval Daver:

Big centers like us, we use it, we have fantastic flow cytometrists who have been working with us, we’ve published on it, we’re comfortable with it. But of course for registration, you need to go to 40, 50, 100 centers, and then it’s just very, very difficult to achieve that. So I don’t know, maybe there are other technologies, duplex sequencing, single cell sequencing every year is getting more and more sensitive. So we may find other complementary approaches that emerge.

I mean, one last thing I would mention from ASH that I thought was very interesting data was from the British group, Nigel Russell and Richard Dillon, et cetera, where they actually took NPM1-FLT3 younger patients, not older patients, but let’s say below 60 I think was the cutoff who got intensive chemotherapy. This was the AML19 study and then they looked at the outcome by transplant or non-transplant using NPM1-MRD.

So these are all patients who had NPM1-FLT3, about 50% of them FLT3-NPM1, but they depended on the NPM1 as the MRD marker because there’s been a longer mature data set of NPM1-FLT3 MRDs just coming from the last three, four years. They said that if you have this patient NPM1-FLT3, you gave them induction with or without a FLT-3 inhibitor, and they achieved NPM1 10 to minus five, was there as a sensitivity negativity, whether they went to transplant or not, what was the outcome? They actually showed that there was no difference in outcome.

So it’s the first time, not just maintenance post-transplant, but also could you make a decision for transplant or not using molecular testing in AML? So it’s one study, it’s not going to immediately change practices, but I do think that in the future there may be patients where we could use molecular testing to even decide this patient may not need transplant and have the same outcome, which is huge because transplant is very expensive, very toxic, very time consuming.

So this is kind of what ALL has been doing for the last 8-10 years, and we’re starting to scratch the surface, I think.

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

That’s fantastic. All right, so let’s end on a positive note -sparing patients from transplant.

Dr. Naval Daver:

Exactly. Exactly.

Dr. Sanam Loghavi:

Thank you so much for your time and expertise. This was highly educational for myself as well.

Dr. Naval Daver:

Thank you. Thank you.