Educational content on VJHemOnc is intended for healthcare professionals only. By visiting this website and accessing this information you confirm that you are a healthcare professional.

The Lymphoma Channel is supported with funding from AstraZeneca (Diamond), BMS (Gold), Johnson & Johnson (Gold), Takeda (Silver) and Galapagos (Bronze).

The Multiple Myeloma Channel is supported with funding from BMS (Gold) and Legend Biotech (Bronze).

VJHemOnc is an independent medical education platform. Supporters, including channel supporters, have no influence over the production of content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given to support the channel.

The CAR-T process represents a novel treatment approach for hematologists. As a significant proportion of the process is conducted at specialist centers, it is key to thoroughly educate the community to ensure patients get referred and managed optimally throughout their treatment journey.

Learning Objectives:

Practical Considerations for CAR-T Therapy in Hematological Malignancies

June 25, 2024 – June 25, 2025

Jointly provided by Partners for Advancing Clinical Education (PACE) and Magdalen Medical Publishing Ltd

- Estimated time to complete the activity: 90 minutes

Target Audience

This activity is intended for physicians and other healthcare practitioners who care for patients with multiple myeloma, lymphoma, or acute lymphoblastic leukemia who receive CAR-T therapy.

Instructions for Credit

Participation in this self-study activity should be completed in approximately 1.5 hour(s). To successfully complete this activity and receive CE credit, learners must follow these steps during the period from June 25, 2024 through June 25, 2025:

- Review the objectives and disclosures

- Study the educational content

- Visit (https://paceducation.com/CE-CME/oncology/practical-considerations-for-car-t-therapy-in-hematological-malignancies/40402/evaluation)

- Complete the activity evaluation

Faculty

David Maloney, MD, PhD, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA

Sarah Nikiforow, MD, PhD, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA

Kai Rejeski, MD, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY

Saurabh Dahiya, MD, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

Shannon Maude, MD, PhD, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

Nirali Shah, MD, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

Bijal Shah, MD, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL

Claire Roddie, MD, PhD, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Jae Park, MD, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY

Krina Patel, MD, MSc, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX

Doris Hansen, MD, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL

Susan Bal, MD, MBBS, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL

Caron Jacobson, MD, MMSc, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA

Michael Jain, MD, PhD, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL

David Miklos, BSc, MD, PhD, Stanford University, Stanford, CA

Loretta Nastoupil, MD, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX

Noelle Frey, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Rebecca Gardner, MD, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA

Yi Lin, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

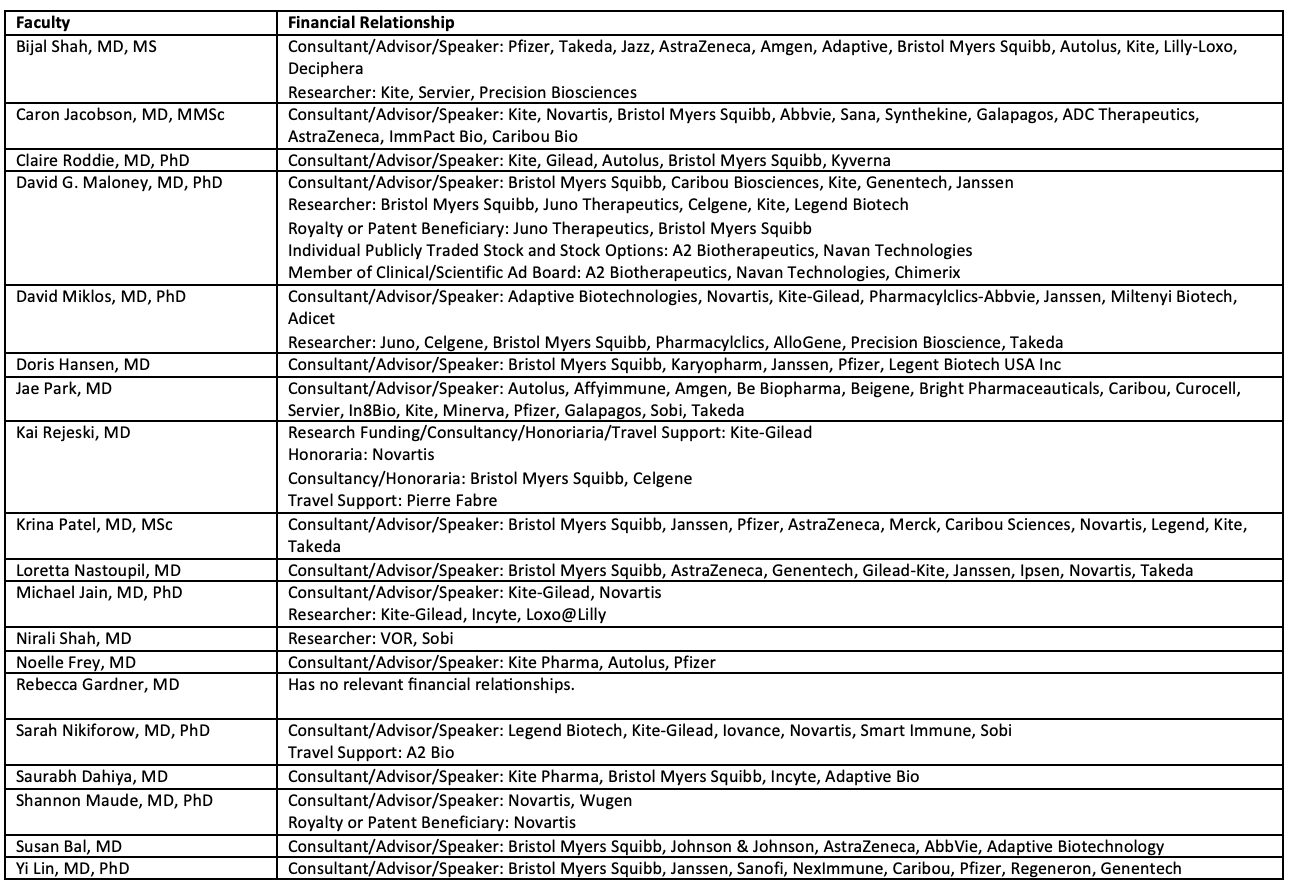

Disclosures

PACE requires every individual in a position to control educational content to disclose all financial relationships with ineligible companies that have occurred within the past 24 months. Ineligible companies are organizations whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, re-selling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients.

All relevant financial relationships for anyone with the ability to control the content of this educational activity are listed below and have been mitigated according to PACE policies. Others involved in the planning of this activity have no relevant financial relationships.

Joint Accreditation Statement

| In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Partners for Advancing Clinical Education (PACE) and Magdalen Medical Publishing Ltd. PACE is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team. |

Physician Continuing Education

PACE designates this enduring material for a maximum of 1.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use

This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. The planners of this activity do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of the planners. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

Disclaimer

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patient’s conditions and possible contraindications and/or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

For additional information about the accreditation of this activity, please visit https://partnersed.com

Practicalities of CAR-T therapy for patients with multiple myeloma

Yi Lin (00:07):

Good morning. I am Yi Lin from Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and we are here at iwCAR-T 2024. And I’ll let my colleagues introduce themselves here.

Susan Bal (00:19):

Hi, I’m Susan Bal from the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Doris Hansen (00:23):

Hi, I’m Doris Hansen from Moffitt Cancer Center.

Krina Patel (00:26):

And I’m Krina Patel from MD Anderson in Houston, Texas.

Yi Lin (00:30):

We are very excited to present the latest data on CAR-T and bispecific antibody in patients with multiple myeloma. And here, today, we will talk more about CAR-T. Very exciting, earlier this month we had approval for both cilta-cel and ide-cel for earlier lines of therapy for patients with multiple myeloma. And would like to hear from your guys’ perspective in terms of how you’re thinking about where CAR-T fits now in the treatment landscape and what particular patient you would think about for the treatment of CAR-T. And we can just start with Dr. Bal.

Susan Bal (01:14):

Sure. I think it’s really exciting to see that CAR-Ts have made their way into earlier lines of therapy, and one of the biggest challenges for our field that we had from the get-go was patient selection. And I think this new approval will make that even more of a challenge in the sense that we’re going to have to make some decisions about who’s the right patient for the CAR-T slots. Because as you know, manufacturing and access will likely become an even bigger challenge with the larger pool of patients that are now going to be eligible for it.

Susan Bal (01:53):

So, while this is a great opportunity, I think it comes with some initial learning and growing challenges regarding patient selection. But certainly, those patients who are at highest disease risk and those who’ve been triple class exposed in their first line of therapy would be ones that I would prioritize.

Yi Lin (02:12):

Dr. Hansen, I know you led a lot of the study with Dr. Patel as well for the US Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium. So, a lot of experience from what we’ve seen so far, for a patient who’s had access to CAR-T in the real world population. So, how are you thinking about the type of patient that you would like to see to get CAR-T in this new approval landscape?

Doris Hansen (02:36):

So, I think it’s very exciting times in myeloma currently, I feel like our landscape is really changing. Earlier approval of CAR-Ts is exciting from KarMMa-3 and CARTITUDE-4 in the sense that patients have the opportunity to get this treatment earlier in their disease course. It certainly does lead to deep and durable responses, which is exciting, but we have to be careful about the safety profile of these therapies earlier in the disease course.

Doris Hansen (03:04):

It is exciting in the sense that you have this one-and-done treatment approach and then patients have this treatment-free period. And what I look forward to is being able to take patients to CAR-T without having to perhaps worry as much about bridging, because if we give it later in the disease course, bridging or keeping the disease stable or at a lower level, so that we can have better outcomes, has been a bit more difficult in the later line. Although, as I mentioned, safety is at the forefront. So generally, the patients I may consider to move forward would be those who have high-risk disease or those who may have more aggressive disease biology earlier on in the treatment course.

Yi Lin (03:44):

And Dr. Patel, what would you like the referring providers to know or think about? And I know you have a lot of experience in that area and have spoken out publicly about what are the key factors to consider for patient referral, to successfully get them to CAR-T treatment.

Krina Patel (04:04):

Yeah, no, I think everything you guys have said is perfect, what we’ve been dealing with the last three or four years. But again, the exciting thing is more patients have access now, right? In second, third line, there’s more patients that actually can get to second to third line and be able to take these treatments. So, I don’t think logistics, as much as they are a pain for us, should be a reason that our referring physicians don’t send patients to us.

Krina Patel (04:24):

So, I think, ideally, I would like patients to be referred one line prior to when those patients are eligible. So, for cilta-cel being in second line, it’d be great that as they’re getting their induction therapy and hopefully doing well, they’re referred to us, so that we can at least start talking about CAR-T, explaining what it is, making sure this patient is eligible.

Krina Patel (04:43):

And I think that I still agree that, as I’ve said before, that eligibility is not like transplant. More patients are ineligible for transplant than I think they are for CAR-T. And again, with our real-world data, we’ve shown we can do ide-cel in patients with heart failure, with renal failure, on dialysis, patients with history of neuro disease, patients with plasma cell leukemia. All the patients that we could not put onto trials, we actually are successfully able to give them these treatments that they didn’t have access to before, and I think that’s really important.

Krina Patel (05:13):

So, I don’t want physicians to think that there’s certain groups of patients they shouldn’t send to us. I think they should send them to us, and then, we are happy to put them in line or at least explain, start the education process, because that is a long-term investment in our patients, to make sure they can go through this in a fair way.

Krina Patel (05:29):

And I think in the end, it’s the overall survival. Right? I don’t have data yet. We don’t have data to show that overall survival is going to be better because of CAR-T, but I have a hint that compared to any other therapy we’ve had, that this will actually improve overall survival. So, even though we can’t necessarily say we can cure patients yet, and we probably can’t, most of them, with these therapies, I think they’re going to be able to live longer and then will need more therapy down the road. So, it’s a shared decision-making and treatment plan for these patients to give them the best outcomes.

Yi Lin (05:59):

Is that true for you guys, too? You’d rather hear about the patient, not worry about having the primary hematologist at home taking care of the patient, do any specific pre-screening, it’s more of a shared patient decision-making model?

Susan Bal (06:17):

Yeah. I would say that I think it’s very important that we start thinking of it as we do for referrals for transplant, but even more generously so. So, all patients that are newly diagnosed, I think should have the opportunity to be seen at a larger academic center, particularly that with capabilities for CAR T-cell therapy, and really make that a decision that’s shared between the physicians at the center and the patient for that decision-making process. And really, it’s no different for our field, because traditionally this has been done for transplant, but I would say even moreso, it’s more important for us to see those patients and really make those decisions in real time.

Doris Hansen (06:57):

Yeah, I fully agree with my colleagues. I think this decision about CAR-T is loosely, essentially easier on us in the sense that everybody, or most folks, should be eligible, particularly earlier in the disease course, as Dr. Patel noted. A lot of the patients we have treated would definitely not have met trial inclusion criteria. We’ve treated patients, as you noted, with cytopenias, poor performance status that may be disease-related, or organ dysfunction, organ failure, renal insufficiency that is myeloma-related. So, I think, definitely a shared decision-making and it would be nice to see these patients earlier on, so we can discuss about eligibility and the appropriate timing for moving these patients forward in their treatment.

Yi Lin (07:44):

Yeah, that’s wonderful. And now that we hope there’ll be more patients who can be getting these CAR-T therapy, there’ll be more patients who will be returning home and working with their primary hematologist for a longer-term follow up.

Yi Lin (07:58):

So, from all of our experiences, while the treatment center are going to be really primarily involved in that management in the first months with cytokine release syndrome, those early neurotoxicity syndromes. What would you like the community or broader oncology practice hematologists be aware of and know about long-term monitoring needs for these patients?

Susan Bal (08:25):

So, one of the most important things that we deal with are hematologic toxicities. So, low blood counts that are common, and these really come in a few flavors. So, the early low blood counts that we see in the first month, those typically are related to the initial chemotherapy that we administer before the CAR-T cells, and those typically recover in the first four to six weeks. And so, usually, by the time they’re going back to their community provider, those have resolved.

Susan Bal (08:54):

But in about less than a quarter of the cases, these will be persistent, and those are some instances where use of growth factors and additional therapies and even consideration of stem cell boost, which has been shown to be safe in this population, is something that the physician needs to be working closely with the tertiary care center where they received their CAR-T. So, that would be a big one. And I’ll give my colleagues opportunities to comment on other things.

Doris Hansen (09:20):

Yeah. So, I fully agree, I think cytopenias appears to be the most common side effect from these therapies. So, depending on where the patient is in their counts, we certainly will monitor some closer than others and we’ll advise on transfusion parameters, which would be common as what we would normally do in community practice.

Doris Hansen (09:41):

Certainly, as Susan mentioned, growth factor support may be needed and that is again, a shared discussion or decision if that is something that may be indicated, as well as stem cell boost. But other consideration for toxicity management would be,s perhaps, delayed neurologic toxicity. So, there may be some very small percentages, but things like cranial nerve palsy or even sometimes Parkinsonian features, and this is something that we commonly would see, perhaps, around a month or so following treatment. It is in a very small percentage of patients, but we need to be aware and work together to be able to identify and manage these types of toxicities.

Krina Patel (10:24):

And I think the big one though, I do think, besides cytopenias is infections. Right?

Doris Hansen (10:29):

Infections. Yeah.

Krina Patel (10:31):

That is something we are seeing a lot more of in our novel therapies. Now again, was this because these were more relapsed/refractory patients that we were starting to treat? Now that we’re doing it earlier, there’s still a sign of an infection. We see that, maybe not as much COVID, but when my patients get COVID post-CAR-T, that’s where it’s detrimental. So, I think it’s really important that we talk to our patients about all these different viruses that are out there, including COVID, that they are vaccinated as much as possible, that if they have symptoms, we treat them with the therapies we have available, because the folks who are still getting bad outcomes are the patients on CAR-Ts and bispecific therapies.

Krina Patel (11:10):

And I think the other big thing is the prophylaxis. Right? We have lots of guidelines now that are out or coming out, explaining all the things we do for PJP prophylaxis, VZV for some patients, IVIG every month, every couple months. The GCSF, of course, helps as well. But we’re knocking down lots of different immune arms at the same time. Thankfully, usually, about six months after is where I see my patients really recovering, some patients will need it longer, but once their IgG levels are sort of stabilized, or they’re six months out, they tend to do a lot better with infections.

Krina Patel (11:45):

So, I think it’s really monitoring them really closely for those first six months, but then even later, taking any symptoms that they have for infection seriously and diagnosing it as to what kind of infection it is. Usually, we see viral infections, but we see bacterial infections, and rarely, fungal infections as well. So, it’s just diagnosing it and then treating it appropriately.

Yi Lin (12:05):

So, just thinking about everything we’ve talked about for the myeloma session here at iwCAR-T, what is something that you would be really looking forward to in this coming year that we may be talking about next year at iwCAR-T 2025?

Susan Bal (12:21):

I think I’d be most excited about some of the novel targets, as well as combination strategies that are now becoming apparent, and understand better how sequencing and combination of different targets can potentially lead us towards more sustained and prolonged remissions. So, I think that’s something that I’m really excited about.

Doris Hansen (12:41):

Yeah. And in those same lines, I’m very excited about new targets, but also combining these targets, so to see the dual and trispecific options in terms of these novel immunotherapies, and how do we give them? Can perhaps, as Susan mentioned, the combination of them or utilization of them in different courses of the disease, will we get to the desired remission or desired cure at some point? So, very excited to see where we head in the next year.

Krina Patel (13:14):

Yeah. I don’t think we’ll have data yet for our upfront trials, which I’m excited to see that when that happens, will we beat transplant, especially? Right? That’s been a long, long, decades-long question we’ve been asking. So, we won’t have that data.

Krina Patel (13:27):

But I agree, the combination data, different mechanism of action versus do we use CAR-Ts against two targets or bispecifics, like the RedirecTT-1 study, long-term data from that. I think, maybe other cells, we heard about NK cells from some of the other groups discussing the other disease treatments, will we ever have that for myeloma? I know there’s some small studies going on right now.

Krina Patel (13:48):

And then, I think, we won’t get this in the next year, but really, can we cure myeloma? We’re still in that. Let’s get better mortality, morbidity, long-term outcomes, but can we get a cure fraction? And I think, in the end, that’s really what we’re all hoping to do with all these therapies we have.

Yi Lin (14:05):

Yeah, actually, that leads me to one final question I have, it didn’t quite come up yet in the conversation is, in today’s landscape, based on what we know with bispecific antibody and CAR-T, how are you thinking about where to sequence that and how to use that in your patient? Right? Presuming it’s available for that patient at that time point of care.

Krina Patel (14:31):

I can start. I have a lot of thoughts on this topic and I have strong feelings on this topic. So, I think, again, I think they’re both amazing. They have different advantages, right? Bispecific, off the shelf, I don’t have to worry for 4, 6, 8 weeks for cells to come back, keeping someone’s disease under control. But being off the shelf, it does have a little bit lower response rate compared to our CAR-Ts. PFS, in general, seems to be shorter and we can argue about that- none of these have been head-to-head compared, so, no one has the data. But in my anecdotal experience, I think this.

Krina Patel (15:06):

But I think that the issue is that because these don’t cure patients, it’s really important that we look at PFS1 and PFS2, and not just response rates, because that can throw you off. We don’t know much about the mechanism of resistance with BCMA, why people start relapsing. Is it the T-cells? Is it the BCMA? We know some data. And I think the idea of bispecifics causing mutations, and also T-cell exhaustion, if you try to make CAR-Ts after that, your response is going to be lower. And it has been, the PFS has been three to six months compared to the 12 to 33 months that we’ve seen in patients who didn’t have prior BCMA.

Krina Patel (15:42):

Versus the other way around, if you get CAR-T first and then a bispecific, the response rates are about 10%, or so, lower, PFS is a few months lower, but it’s not as dramatic as the other way. And again, looking at PFS1 and 2, your patients are actually going to live longer and do better if they get the CAR-T first, because they might not get CAR-T if they’ve gotten bispecifics for a long time ahead of time. I think there’s an idea of maybe we hold it for six months and hopefully the T-cells come back, maybe the BCMA comes back, possibly. But do our patients have that time, especially in the relapsed refractory setting? I think some of that, now that CAR-T is available first, hopefully we’ll take that out for some of our patients. But I think we really need to look at the entire landscape and not just the one drug at that time.

Doris Hansen (16:26):

Yeah, I fully agree. We have done some studies. I mean, obviously, the data here is a bit scarce in the sense of sequencing BCMA therapies, but we have done, as you noted, real-world studies looking at patients who have received prior BCMA therapy before receiving CAR-T. This data was with ide-cel. And what we found is that patients who have received belantamab, which now is off the market, or other bispecifics on clinical trial, they had a inferior response rate, as Dr. Patel noted, but they also had an inferior progression-free survival. And there’s been a small amount of data as well on CARTITUDE-2, or the clinical trial with cilta-cel, essentially also showing the same thing, that patients who have had prior BCMA exposure, they have inferior response rates.

Doris Hansen (17:11):

We also have done some data looking at outcomes the other way around. So, essentially, looking at patients who were relapsed from ide-cel and received teclistamab after. And what we found is that these patients do respond to immune engager, and the response, although it may not be as good as not having had prior BCMA exposure, it’s still above 50% and the patients do quite well.

Doris Hansen (17:34):

So, based on the evidence and data that we have thus far, it does appear that CAR-T first, bispecific second, may be an approach that is feasible and patients will respond. But certainly, now we have another bispecific that targets a different area on the myeloma cell, talquetamab, that hopefully patients will have many options. So, very exciting where the field is heading.

Susan Bal (18:02):

And I would agree with my colleagues completely, I think it seems that at least from the data that we do have, that that seems to be the optimal sequence. And what we have to remember is that one of the key things that helps us understand how patients will do is that time from each BCMA therapy to the other.

Susan Bal (18:19):

And as Dr. Patel mentioned, sometimes we don’t have the opportunity when patients are relapsing on a bispecific, to decide about CAR-T, they really need to go at that time. And so, whereas, when you receive a CAR-T first, you have this inbuilt time off treatment due to the one-and-done nature of the CAR-T, that builds in that time. So, that remission is already that time off from that therapy, which perhaps can re-sensitize some of those patients, and I think, at least based on the data we have, appears to be the right sequence.

Yi Lin (18:50):

No, absolutely. And it’s, I think, very important to consider keeping other treatment options open for the patient. So, CAR-T before bispecific, if possible. But we may also start to learn instead of using bispecific until patients progress, where we have some data about T-cell exhaustion and what that looks like at the time of progression is, is there potential opportunity to use bispecific almost more as a bridging to CAR-T? And would that be different than what we see if you use bispecific until patients progress? So, hopefully, more data to come with that as well. Yeah. All right. Well-

Doris Hansen (19:31):

Yeah. We are looking at that very question and, hopefully, we will have some data shortly with utilizing talquetamab bridging before CAR-T. So, very exciting.

Yi Lin (19:42):

Yeah, that sounds great. Sounds like we’ll have more to talk about at iwCAR-T 2025. Thank you very much.

Practicalities of CAR-T therapy for patients with lymphoma

Loretta Nastoupil (00:07):

Hi, I am Loretta Nastoupil and it’s been a privilege to participate in this iwCAR-T meeting here in Miami in 2024. And it’s been a great honor to have with me two esteemed colleagues. I’ll turn it over to you, Mike and Caron, to go ahead and introduce yourselves.

Dr. Michael Jain (00:23):

Thank you, I’m Michael Jain, and I’m a medical oncologist at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida.

Caron Jacobson (00:28):

I’m Caron Jacobson. I am also a medical oncologist and lymphoma clinician at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

Loretta Nastoupil (00:37):

All right, so we’re going to jump right in. So at this meeting we saw updates to the pivotal studies that led to FDA approval of CAR-T for the management of follicular and large cell lymphoma, real life experiences we’ve learned now that we’ve had a couple of years utilizing these agents, and then sneak peek into where we’re headed in terms of future directions. I guess, Mike, I’ll start with you. What have we learned over the last four years, now that we have FDA approved products and we’re using them in maybe broader patient populations than they originally studied?

Dr. Michael Jain (01:05):

So for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which is the most common aggressive lymphoma, there’s now FDA approvals for different types of patients, but it’s mostly in the second line. So most relapses when patients get their original frontline therapy like R-CHOP, most of the relapses happen in the first year, and that’s where CAR-T cell therapy is mostly approved. So if your lymphoma comes back within one year of R-CHOP, then you’re eligible for either axicabtagene ciloleucel or lisocabtagene maraleucel as CAR-T cell therapies. It’s also approved for patients who are transplant ineligible with liso-cel or lisocabtagene maraleucel if you relapse beyond one year and you just don’t have a transplant option. So that’s the main setting in which we’re using CAR-T cell therapy now for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which is in the so-called second line setting.

Loretta Nastoupil (01:51):

And Caron, what have you learned in terms of getting patients referred in? Who’s an optimal candidate? Who do they refer them to?

Caron Jacobson (01:58):

Yeah, these are excellent questions because before we had these approvals, CAR-T cells were approved in the third line and beyond. And I think there you had a lot of runway to meet the patient, get them into clinic, because generally they were referred at the time of first relapse. And so patients would come in, they would then get their second line of chemotherapy and then you would pivot from either auto or CAR depending on how they responded to that second line, I think. And a unexpected challenge with the second line approvals is the fact that these patients are now coming in either with primary refractory disease or rapid disease relapse and you’re trying to get them to CAR without that six weeks of interim therapy. And so I used to advise referring physicians to send people in one line of therapy before CAR was indicated, but that would mean referring every large cell lymphoma patient.

Caron Jacobson (02:50):

I think now I’ve modified that to say that I think high-risk large cell lymphoma patients at diagnosis should be referred in at some point during their frontline chemo-immunotherapy. The earlier the better because we have lots of frontline trials at our centers, either with CAR or with some of the newer therapies. And so those patients could be eligible for those trials and certainly for all large cell lymphoma patients where if your center does interim CAT scans or PET scans, has had an insufficient response to therapy at that point. Not that I would stop therapy as long as they’re responding, but at least you know that those patients may need to pivot to CAR pretty quickly. And that allows our centers to get these patients in, to get to know them, and then to hit go as soon as we know that it’s indicated.

Loretta Nastoupil (03:38):

And Mike, there’s competing treatment considerations. We’ve got years of experience of identifying who’s not an optimal candidate for high-dose therapy autotransplant. How do you paint the picture for someone that is a candidate for CAR-T for the average community doc?

Dr. Michael Jain (03:55):

Right. So what we’ve learned is that CAR-T cell therapy is very effective and probably the most effective therapy a patient can get. And regardless of some of the other things that are going on for the patient, lymphoma control in these aggressive diseases is the most important thing. And one of the things that we’ve learned is that probably some of the comorbidities or older patients that we used to worry about, those factors seem to be we can manage them. Poor renal function, older age, all of those patients can get CAR-T cell therapy. And so we’re getting a lot better at getting everyone this potentially curative therapy that we think will really help them and having these patients go through the process.

Loretta Nastoupil (04:35):

Caron, there’s a lot of discussion about perceptions regarding the acute toxicity with CAR-T. What strides have we made recently to try and maybe mitigate some of those concerns?

Caron Jacobson (04:44):

Yeah, I think the acute toxicities that of course we’re talking about are cytokine release syndrome or CRS or the neurologic toxicity, which also goes by the name, ICANS. And these are toxicities that happen within the first one to two weeks after CAR-T cell therapy. They are observed for and treated at the CAR-T Cell Treatment Center, so less of a concern for community physicians once the patient goes back into the community.

Caron Jacobson (05:12):

And what we’ve seen as we treat more and more patients, more and more patients who have comorbid disease and other end organ dysfunction from other causes, is that we’re seeing the same excellent response rates, but we’re not seeing an increase in these toxicities. In fact, we’re seeing them decrease over time. And the reason for that is that we have learned to intervene at earlier time points. So in some cases that means using prophylactic steroids for very, very high risk patients early on in their CAR-T cell treatment course. And for others, that just means more aggressive management with corticosteroids, with tocilizumab.

Caron Jacobson (05:47):

There are a number of studies looking at using a variety of cytokine modulators to prevent these toxicities. I don’t think any have been incredibly convincing at this point. And so they certainly haven’t made their way into our management algorithms, but I think we’re continuing to learn from those studies and figure out what the next cytokine modulator might be that could make their way into our treatment paradigms.

Loretta Nastoupil (06:11):

And Mike, what have we learned about the late toxicity since we might be sharing these patients with those community docs, what do they need to be on the watch-out for and what strategies could we suggest to mitigate those?

Dr. Michael Jain (06:22):

Yeah, so for me, I really like to share the patients with their local doctor that they know best and that they’re close to. And so early on we’re interested a lot in relapse. So we’ll stage them every three months or so just to make sure that they are not going to relapse. But most of the relapses, if they happen really occur in that first year. Late relapses are very uncommon. And so as time goes by, we think more about the survivorship of these patients and critical survivorship issues over time or infections.

Dr. Michael Jain (06:49):

These patients often don’t make antibodies because they have what’s called B-cell aplasia, so they may need IVIG or other supportive types of therapies. And then more and more we’re identifying that some of the older patients are perhaps at a higher risk of secondary malignancies, and these patients have had a lot of chemotherapy in many cases in the past. And so following these patients for those reasons appears critical for the long-term survival of these patients. But we now have patients out five, 10 years from CAR-T cell therapy, and so it’s really remarkable in my clinic to see patients who are doing great over the long-term and still connecting with me maybe once a year, but spending more time with their local oncologists for their long-term survivorship needs.

Loretta Nastoupil (07:28):

And Caron, this fall, we saw notice from the FDA regarding concerns about second cancers that may emerge in this unique patient population. And we saw a little bit more of a deep dive here at this meeting. What is your perception about that risk? And again, strategies that may reduce that?

Caron Jacobson (07:47):

So I think we should separate secondary malignancies that are non-T-cell lymphomas from those that are. So the non-T-cell lymphomas are some solid tumors, skin cancers, screenable cancers like colorectal cancer, breast cancer, things like that, as well as myeloid cancers. And those risks, I don’t think we’ve seen convincing evidence that those risks are necessarily higher than the other anti-cancer therapies that our patients have received, although certainly there needs to be a little bit more work done for that.

Caron Jacobson (08:21):

But I think the big elephant in the room is really the T-cell lymphomas. Obviously this is a concern that we had from the beginning because we are doing genetic engineering of these T-cells. There is a concern for insertional mutagenesis of the CAR transgene into an unfortunate part of the genome and whether that could lead to oncogenic transformation of a T-cell. So there are some instances where patients post-CAR are being diagnosed with T-cell lymphomas.

Caron Jacobson (08:49):

It’s incredibly rare right now it’s estimated at about one in 10,000. But the incidences where that… Most of those have not been investigated deeply enough to understand if those are CAR mediated or if those are related to some other risk factor. So of the 20 or so cases that have been identified, only three have been shown to have the CAR transgene. And even in those we haven’t necessarily shown that the CAR transgene has inserted into a place that could have led to the T-cell lymphoma. It could be that this was a clone that was predisposed to develop into a T-cell lymphoma. And we accelerated that by putting it under proliferative stress and then potentially adding further genetic mutations.

Caron Jacobson (09:34):

So the bottom line is, and it’s exactly what Mike had just said, which is that we will tolerate risk for disease, for a therapy that’s going to cure the disease that’s likely to kill the person in that moment, right? So I think this is an incredibly small risk. It’s not larger than the risk of other therapies that we give to our large cell lymphoma patients, and it should not preclude us from referring patients or treating patients with CAR-T cells.

Loretta Nastoupil (10:00):

All right. And so before we move on to other indications, there still are patients that progress following CAR-T cell therapy. So what in your opinion on the horizon looks promising in terms of next steps?

Dr. Michael Jain (10:11):

Yeah, so things have really changed. I remember we did an analysis five years ago and what kinds of treatments people would get after CAR-T cell therapy and the outcomes were very poor. But luckily I’m starting to see some real optimism around for the half or 60% of patients who the CAR-T cell therapy just doesn’t work for them, that they can get other treatments and have in some cases durable remissions.

Dr. Michael Jain (10:33):

And so treatments that are coming out like bispecific antibodies appear to be quite useful for these patients, and recent analyses suggest that patients can get this after CAR-T and still have responses that they might expect to be quite good. There’s other drugs, especially including a drug called polatuzumab that can be quite good for reducing disease burden and perhaps getting people towards a stem cell transplant or other therapies. So I think drug development is really pushing forward in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma for both CAR-T cells and other types of drugs. And I think all of this is good news for our patients, but still for me, CAR-T cell therapy should be delivered as early as possible in these relapsed patients, just because they do have a curative possibility. And for most patients, that’s really what they want.

Loretta Nastoupil (11:19):

Perfect. So Caron, tell us about the indication for follicle lymphoma. Who were the patients where that was studied and where do you consider it in your practice?

Caron Jacobson (11:27):

Yeah, so there are two approved CAR-T cell therapies for follicular lymphoma. There’s axicabtagene ciloleucel, or axi-cel, and tisagenlecleucel, or tisa-cel. And they were both studied in the multiply-relapsed refractory populations. These are patients that have received at least two prior lines of therapy, so they’re being treated in the third line. And this is a group of patients where their follicular lymphoma does start to pose a risk to their overall survival. Many patients with follicular lymphoma don’t need a third line of therapy, will do quite well and will die with their disease, not of it.

Caron Jacobson (11:59):

But I think once we start getting to third line therapy, these really do represent an unmet need where prior to CAR-T cell therapy, most of our drugs led to approximately one year disease-free survival. So that’s the context in which CAR-T cells are approved. And it’s based on really tremendous data from both the Zuma-V study for axi-cel and the Allara study for tisa-cel, which demonstrated very, very high response rates on the order of about 70 to 80 percent complete response rates and really, really durable remissions where we’re seeing that 50 percent of patients remain alive and disease-free four to six years out from their CAR-T cell infusion, which does really approach almost first front line therapy for these patients.

Caron Jacobson (12:49):

And so now of course there is a move to try to move these into earlier lines of therapy. And so there are studies looking at high-risk patients in the second line, so those POD24 patients. But it becomes a little bit more complicated in terms of thinking about the risk-benefit ratio, especially since now we have the CD20 bispecifics approved and in clinical trials for follicular lymphoma because these, like I said, these are patients who live with their disease for a long time. And even though I don’t think that the CD20 bispecifics necessarily have the same durability, offer the-same durability of response, and they do require repeated dosing, that difference in the durability of response or that slight detriment for the bispecifics may be more appealing to somebody who might be risk-averse and not want to see the CRS or the ICANS that we can see following CAR-T cells.

Loretta Nastoupil (13:44):

And tell us about mantle cell lymphoma, Mike. Where do we have an indication? How are you navigating that?

Dr. Michael Jain (13:49):

Sure. So mantle cell lymphoma is, as you know well, another type of lymphoma that is somewhat between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in terms of its aggressiveness and follicular lymphoma. But famously it’s very heterogeneous. So some patients have extremely aggressive types of mantle cell lymphoma and others have disease that sort of is more manageable. And so in this area, CAR-T cell therapy has been extremely helpful because patients who have relapsed or refractory disease who are outside of the front line, often they don’t have great progression-free survival, even with available therapies like BTK inhibitors, especially if they have high-risk features like a p53 mutation or blastoid types of disease.

Dr. Michael Jain (14:28):

And so CAR-T cell therapy is approved for second line or relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Most people wait until the patient has been exposed to at least one BTK inhibitor in the past, although that’s not officially part of the label and so individual times will make a decision for high-risk patients. Maybe we want to treat these patients also, but that’s the main group of patients is in the relapse refractory setting who have had another BTK inhibitor in the past.

Loretta Nastoupil (15:00):

And so I appreciate both of your thoughts about where we’ve come, where we’re headed. So if a patient, Caron, we’ll start with you, is referred to your center and the community oncologist is thinking, “I think this patient might be appropriate for CAR-T,” and all of a sudden you present a clinical trial, tell me what are the next or future directions that would be interesting enough to forego an auto CAR or maybe in someone who’s progressed on an autologous CD19 directed CAR. Where are we headed? What looks promising?

Caron Jacobson (15:26):

Well, so I think in large cell lymphoma we’re starting to see new targets. So we heard at this meeting about targeting CD22 in large cell lymphoma, really excellent data that looks pretty similar to how a CD19 CAR performs as a first CAR therapy, but this is actually in a CD19 CAR relapsed patient population. And so that is now in a multi-center registrational study. So that is a study I would offer to someone who had relapsed after a CD19 CAR, and that might lead to an approval of another CAR for large cell lymphoma.

Caron Jacobson (16:05):

We have CARS against ROR1 now, we have dual antigen targeting CARS that are targeting 19 and 20. So if someone has not seen a 19 CAR and we had one of those studies open, that might be a great study to offer a patient because we think that from the early data and just from biologic plausibility, it seems like they should be just as good as the 19 CARS, but potentially do offer an improvement for those patients who might relapse because of anagen escape.

Caron Jacobson (16:35):

So I think those are some of the most exciting trials to offer these patients at this point. I think there are other trials that are thinking about novel combinations of either combining bispecifics with CAR-T cell therapy, which we saw some data here that shows that that’s both safe and effective. And then also thinking about novel ways to condition the patient so that you can potentially improve T-cell expansion and persistence following CAR-T cell infusion. So, I think that if they’ve never seen a CAR, it would be a CAR plus study and if they have seen a CAR, I think some of the unique and novel anagens are very appealing right now.

Loretta Nastoupil (17:18):

Sure. And Mike, share some thoughts with us about the allogeneic CARS sub-gingerly using healthy donor cells to try and get around some of the limitations of patients who’ve had lots of prior therapy or very suppressive microenvironment. What progress is being made there and what should people be on the lookout for?

Dr. Michael Jain (17:35):

Yeah, so we worry about patient’s own T-cells because with current CAR-T cell therapy as autologous, we take their T-cells and we turn them into the CAR-T cells that are going to fight their cancer in. Oftentimes patients, because of either recent chemotherapy or aspects of their tumor, they have quite poor T-cell quality. And so we worry if we take poor quality T-cells and turn them into CAR-T cells, these patients won’t have as great an outcome. And so there are efforts to do what’s called allogeneic CAR T-cell therapy where you take a young healthy donor who has great T-cells and manufacture those into CAR-T cells. And one of the other advantages is that it can be delivered much faster, and so you don’t have to wait for the individual person’s T-cells to be made into CAR-T cells. They can come directly off the shelf. But what you’re giving away, but the problem with some of these is going to be is that when you take some donor’s T-cells, they may get rejected by the patient.

Dr. Michael Jain (18:27):

And so over time, we’re still trying to understand whether or not newer approaches to design and different things have actually overcome that problem and that the CAR-T cells work just as well as the autologous ones. But one setting which is going to be tested, where it might be the most useful, is in patients who have very little disease burden at the end of their R-CHOP chemotherapy. But we worry that they’re at a very high risk of relapsing because we can still see that minimal residual disease. And so there’s a trial of one of the allogeneic CARS to treat that population. And so a lot’s coming on the horizon for all the people who are seeing these patients. I think Caron made a great point, refer them early. We have a lot of options or at least have a conversation with us because I think we have a lot of new ways of thinking to benefit these patients.

Loretta Nastoupil (19:12):

As you’ve heard, tremendous progress has been made just over the past few years, and I’m very hopeful for the future because I do think that we have tremendous folks just like Caron and Mike that are working really hard to understand where the current limitations are with our FDA approved products and exploit those so that the next few years we’re going to see more and more therapies emerge that will only benefit our patients. So thank you.

Practicalities of CAR-T therapy for patients with ALL

Noelle Frey (00:00):

Hi, I am Noelle Frey from the University of Pennsylvania and I’m here with some colleagues today. And we just finished a very interesting session going over some updates of CAR-T cell therapy for adults with relapsed and refractory ALL. So I’d like to start by interviewing my co-members up here. So we have Dr. Claire Roddie from University College London, Dr. Jae Park from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Dr. Bijal Shah from the Moffitt Cancer Center. Thank you guys for joining us.

(00:35):

We had a really interesting session today and Bijal, I’ll start with you. We all are aware that Brexu-cel is the first agent in the CAR-T cell therapy space to gain an indication to treat adults with ALL. And today you provided some updates on some real-world data. So I’m curious what was added to our knowledge base with that data?

Bijal Shah (01:00):

Well, I think the first thing that was really nice to see was it confirmed what we had seen on study, that’s despite treating higher risk patients in some contexts, meaning a higher percentage of patients with extramedullary disease, folks with active CNS disease, what we see in practice. Interestingly, there was something that occurred in parallel and that was the enrollment of patients with lower bone marrow burden of leukemia. We’ve known for a while that Blinatumomab may work better in that context and we had some hints from the ZUMA-3 trial that maybe we would see less toxicity and added benefit and that appeared to be the case, at least for the safety part. We’re still teasing out some of the efficacy numbers, but early data are certainly pointing in that direction. So it was nice to see that.

(01:48):

I think what to do after CAR-T is still a big mystery. We’ve all had these patients, they’re 27 years old, they are seeing you because they didn’t want to transplant the first time around and now they’ve gotten CAR-T and they’re in an MRD-negative remission after having explosive disease and you’re having that conversation. I think what is nice is we have data that says from the real world, at least in the short term appears that we can improve progression-free survival, extend that remission and maybe that’ll be solace for them, I’m not sure, but it was nice to see.

Noelle Frey (02:22):

And there were also more patients in the real world data set that had CNS disease or extramedullary disease and it seemed that at least preliminarily outcomes are good in that patient population which wasn’t as well represented in ZUMA-3. So in terms of our colleagues that might not be practicing at a center where CAR-T cell therapy is standard, when would you advise somebody refers to a CAR-T or transplant center if they have a patient with ALL?

Jae Park (02:53):

I mean, I think earlier the better. I think the key message from I think the post-ZUMA studies or earlier studies that we’ve done and all the self-studies and the international studies I think all show that the lower burden of the patients, less treated patients fair better both for the efficacy and also the toxicity profiles wise too. So we definitely want to see these patients early for CAR-T cell therapy.

(03:14):

But even before CAR-T cell therapy, I would argue in adult ALL, which is a rare disease that it’ll be better to be treated in the specialized center where you are seeing a lot of ALL patients, ALL expert center because there are choices, there are maybe more than one CARs that may need to be done, but also in addition to CAR Blinatumomab or tocilizumab, there are other agents too. And then CAR-T might be the best choice at the time or may not be the most fitting choice for some. So deciding those is not always straightforward. So even making the decision and also when to collect the cells before they commit to a bridging or second line therapy is also very important. So we’ll rather see these patients earlier than later.

Bijal Shah (03:56):

I want to highlight something important you said, which is not just a specialized center but a specialized center that can deliver CAR-T cell immunotherapy. And I think that is an important distinction.

Noelle Frey (04:08):

Yeah, and I think you mentioned a lot of things where we’re often working together with the referring oncologist and one is, is it the right time to give CAR-T cell therapy? Are there other regimens or treatments outside of the CAR-T cell space that might be helpful? And if we are in the situation where we’re going forward with CAR-T cell therapy, the CAR-T cell therapy physician can really help with bridging therapy decisions that might end up being delivered closer to the patient’s home.

(04:38):

So Claire, we heard a lot about Obe-cel today and why don’t you share with us a little bit about this agent, which is under review for a potential indication, but a lot of us haven’t used it outside of a clinical trial, so share with us some highlights of the agent and the impact it seems to have for adults with relapsed ALL.

Claire Roddie (04:57):

Absolutely. Well, so Obe-cel, it is sort of a different CAR-T cell product to what’s currently on the market and it was developed at UCL, which is where I’m based. And essentially kind of the USP and how it differs from other CARs is the fact that it has a different sort of interaction with the target on the leukemia cell. So in a sense, it only binds for short periods on the leukemia target and we’ve seen in preclinical work that we’ve done that that confers specific biological advantages to this CAR-T cell product in vivo. So for instance, it seems to be associated with a higher proliferation so the CAR-T cell grows really nicely in the patients. And what’s more, it seems to be associated with a lesser toxicity profile, so we see less in the way of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity with this product.

(05:51):

And because it has this sort of different interaction with the target, it means that it doesn’t get quite so… There is the phenomenon of T-cell exhaustion so even the CAR-T cells get tired if they’re forced to do their job for a protracted period. So there’s less in the way of exhaustion, and as a consequence those CAR-T cells can then live for longer periods of time in the patient blood stream. And what that sort of effectively does is those CAR-T cells are like little mini robots continuing to prevent, I suppose, the relapse from the leukemia so that you can see biologically there’s lots of different potential advantages to having a novel construct like this.

(06:26):

So we did test it in a phase one setting and then we’ve gone on to test it in phase two and it’s a global study in both Bijal and Jae were on the study and they were investigators, and what we’ve seen is that it seems to work really well in adult patients with relapsed and refractory leukemia. Not only are we seeing remissions, so we’re getting about 75% approximately of the patients are achieving remission after this CAR, but they’re getting to that point with really minimal immunotoxicity, they’re not getting much in the way of the ICANS, the neurotoxicity, only 7% of patients got the grade three events. So that was really encouraging.

(07:08):

And what’s more, we’re sort of seeing that long-term persistence, the CAR-T cells surviving in the patient blood stream, that’s about 72 to 75% of patients with that ongoing persistence at last follow-up. So all of this is pointing towards Obe-cel being a really good choice for adult patients with ALL and particularly older patients with comorbidities, potentially adults who may not tolerate a more sort of aggressive therapy. And I think I agree with what everyone said before now that we don’t know where we sit in relation to whether patients need an allogeneic stem cell transplant, but I think that’s going to form part of our discussion, I imagine.

Noelle Frey (07:52):

That’s great. And so one of the things I think you were highlighting is with minimizing toxicity, because our adult ALL patients just historically in CAR-T cell development have had a very high response rate, which is great, but that did come along with a greater incidence of more severe CRS and ICANS, and Bijal you highlighted in the real world experience, the severe rates of CRS and ICANS, while still there, are lower. And that’s due to, I think, a better understanding of how to utilize and the timing of intervention when patients get CRS and ICANS with corticosteroids and tocilizumab, and you highlighted with just the construction of the product, just the biological activity might predict for less overall toxicity. But these severe side effects still occur. And Jae, I know you’ve given a lot of thought to how we manage this toxicity in the current space and just wondering if you can shed some light on some future directions or other ways to manage these toxicities.

Jae Park (08:56):

Sure. So I mean, the good news is that I think the one thing I think we want to emphasize and especially for this audience too, is that I think adult ALL patients got probably the worst reputation getting the most amount of toxicity, and we don’t want them to be necessarily deterrent of not being referred because we do want to see patients, and obviously with Obe-cel and others, one thing that’s getting better is the toxicity rates. So it’s no longer super toxic or most patients can make, it’s still 25% of the patients are not able to proceed with the CAR-T test because we’re seeing these patients maybe a little bit too late and not so much of the toxicity rate.

(09:31):

So having said that, so it is getting better, I think the management is definitely getting better for a variety of different reasons. The product is improving, the patient selection is getting better. But the other thing is understanding of some of the pathophysiology is also improving as well too, kind of what is causing some of these toxicities. There are more understandings that we had for the CRS cytokine release syndrome and including IL6. Neurotoxicity, there have been several preclinical studies and also translational studies looking at the patient samples, kind of looking at, what are the cells or if there are any cytokines that might be particularly responsible for this neurotoxicity? And interleukin-I has to be one of those such cytokines that gets elevated very early. So we started using IL-I receptor inhibitor and a key line prophylactically to see whether we can prevent severe neurotoxic rates in lymphoma patients, because some of the products can still cause about 25% rates of a severe eye cancer rate, neurotoxicity rate in lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma patients. So it certainly could be applicable for ALL patients as well too.

(10:31):

So now we have the tools even better to certainly management of a neurotoxicity, but what we want to do better at is actually to prevent them, so not only the patient’s selection but now with some of this specific cytokine blockade that we can prevent this the severe neurotoxicity, which continues to remain as one of the major concerning side effects of our patient population, but it is improving with all these management skills.

Noelle Frey (10:55):

That’s great, so I think we are making advances in some of these very serious short-term toxicities. And I think it used to be the fact, and I’m guilty of this myself, where I’m like, you get to day 28, you don’t need to worry about toxicities anymore. But I think with longer follow-up and fortunately patients staying in remission and living longer, we’re learning more about some of these long-term side effects and that can really impact how our colleagues will follow these patients after they leave our center. And so I think one thing comes to my mind immediately, which is we actually like it when the CAR-T cells persist, but that can lead to B-cell aplasia, hypogammaglopulinemia, and so patients might require IVIG replacement. And I don’t think we have that ironed out exactly how to do that, but that’s a potentially years long intervention. And then cytopenias came up too, so I was just interested in how you guys recommend, when you’re discharging patients from the practice, how you recommend your colleagues in the community follow these patients going forward?

Bijal Shah (12:06):

Well, I’ll take a bite. One, I don’t discharge them from my practice.

Noelle Frey (12:10):

I like that.

Bijal Shah (12:12):

One of the things that, maybe it drives my team crazy, but I’m still seeing them five years later. The approach to the hypo-

Noelle Frey (12:24):

What if they live very far away though, or how do you manage them, I guess?

Bijal Shah (12:26):

Yeah, telemedicine honestly, I really try to maintain that follow up. The Bactrim and the acyclovir, those are the easy pieces and I think most patients are comfortable with that and we’re following them for T-cell recovery. The hypogam, as you pointed out, is more difficult, not because we don’t know what to do, it’s because the insurance companies don’t know what to do. And I think that’s been the bigger struggle is we’re using a cutoff of 400 for the IgG, which is fine, but there are some people who are getting infections at 500 and 600.

(12:54):

And so fighting these battles is still something we have to do. My wife’s an immunologist so I have a little bit of an advantage in terms of getting some things approved, but it’s still a lift and I think that’s hard. How much to give, when to give, we heard from one of the speakers at the meeting earlier today doing it high dose for five days in a row, it’s not something I’ve ever done. I am not sure even how to sort of put that in perspective, but we are seeing infection. When we look at our longer term results, which I didn’t present today, infection is a leading cause of mortality in our patients.

Claire Roddie (13:31):

I mean, the IVIG question is significant, but it’s not just intravenously administered, not forgetting that there is a way to make it sort of more acceptable to the patient and their family, but with subcutaneous administration, they can be taught to do that at home. We have really stringent criteria in the UK for eligibility for IVIG because it’s such a precious and limited resource and we’ve had to institute alternative mechanisms to keep our patients sort of free from bacterial infection or to try and prophylax them. So we have strategies to sort of use doxycycline prophylaxis for people with recurrent chest because we can’t get IVIG for everyone. And the other thing to build into your practice, if there are limitations in insurance policies or insurance companies are resisting giving it, you can build in IVIG holidays as well, so for instance, during the summer months where you’re infectious profile, you tend to be less susceptible. So there are ways of limiting the kind of overall volume of IVIG you’re using that’s more maybe acceptable to your insurance payers.

Noelle Frey (14:34):

Yeah, I-

Jae Park (14:34):

Sorry, I was just going to add though because the reality is that as much as we want to keep these patients, some patients at the end of the day don’t want to come to the city and cross the bridge into Manhattan where I practice. So what we typically have done as kind of the service is that we try to give it some instruction best as we can as a discharge summary so that note can be faxed to their treating investigators. Some of the things that infection-wise, and it’s not perfect because the rules are changing, but these are the things to watch out for the late infections, the common late phenomenon and things like that or how to check the IgG and then it’s a little bit easier to get IVIG in the US but still if you don’t check it, you don’t know and you don’t give. I also recently got a PJP infection, some of the patients who returned to community and came back and almost could have died and was in ICU and so forth, but luckily survived and did well. But these events could happen so we tend to emphasize them in the point and educate the patients to discuss these with your doctor, but if they do forget, we write them down at least so they have something that can be communicated to the treating doctor, local oncologist.

Claire Roddie (15:37):

I think there is a similar process in the UK as Bijal is saying is because there are some patients who refuse to come to the center, I think it is important to maintain a kind of, not just from the individual patient perspective about their sort of welfare and so on, but it’s also for the kind of education of the CAR-T cell center as well. It’s picking up patterns and late toxicity because we recognize that TRM is infection driven and it’s not happening all within the first 28 days, but we are seeing late PJPs. We’ve had a new core arise, we have all sorts of atypical viral infections.

(16:07):

And the thing is that all sort of disappears into the community if we don’t have some way of reaching out. But we’ve developed shared care models and I think that’s not a system that works really well. So we have sort of email correspondence with the local clinicians who will organize blood tests and so on and then we will interact based on phone consults and give advice and we have services that are led by clinical nurse specialists so it doesn’t necessarily need to be Jae sitting on the end of the phone for 12 hour stretches, it can be his colleagues who deliver a service like that.

Noelle Frey (16:38):

Or we could all be as charming as Bijal and then our patients would just keep coming back.

Bijal Shah (16:43):

I don’t think it’s charm. But there is one other thing that I do and it’s very off-label, because I want to make sure I clarify that for this particular venue and that is I’ve started substituting fludarabine for cladribine and we’ve seen earlier B-cell recovery less in terms of the prolonged cytopenias and same spectrum of toxicity when we talk about CRS and ICANS, so we are not seeing any impact there and certainly no impact on efficacy that we’ve been able to pick up with a year and a half of so of follow up. And so it’s been a nice alternative.

Noelle Frey (17:21):

Yeah, and I think we saw that message a lot in some of the earlier talks today. Lymphodepletion is something that we actually have control over and we saw different outcomes based on lymphodepletion, so that’s another area to potentially make an impact.

(17:38):

So I think one of the final things to talk about is we’ve all been so positive, but unfortunately relapse remains. I think one of the biggest challenges, we do have patients that are cured with durable responses, we talked a little bit about how a consolidative transplant in somebody who’s transplant naive and the appropriate patient is appropriate to think about because of some trends towards improved survival. But we kind of think of relapse in two big flavors. So there’s the CD19 positive relapses, and then the CD19 negative relapses from escape. And so what are some strategies that are being investigated that you guys are excited about to try to mitigate that?

Claire Roddie (18:23):

Well, I can talk briefly to that. So just in terms of the approach to stem cell transplant consolidation, first of all, to mitigate and potentially prevent relapse, obviously we’ve identified through the FELIX study of Obe-cel that there are a couple of patient cohorts that would appear to be at higher risk of early treatment failure and those are patients with exceptionally high burdened disease prior to lymphodepletion, so that’s more than 75% blast, and patients additionally with extramedullary disease and other groups have also identified the loss of the CAR-T, a surrogate for that being the loss of B-cell aplasia within the first six months post-treatment as being a sort of strong predictor of relapse. So in those sort of biologic situations, one could argue for a consolidation therapy. So whether that’s an allogeneic stem cell transplant, that’s decision one, and not everybody’s fit, not everybody’s of the right age and not everybody has a matched donor. So it’s not without its own challenges.

(19:21):

In the pediatric setting, our colleagues in the UK are slightly ahead of the curve above us adult physicians and they’ve actually looked at reinstituting standard sort of UCAL style maintenance therapy and they published quite recently in Blood Advances looking at that and shown sort of like a comparable outcome to the use of allotransplants. So they had a cohort who received transplant versus maintenance and the maintenance was instituted with loss of B-cell aplasia. So preventing relapse. So I think there may be alternate strategies that it’s not sort of allo or nothing, I think there probably will be alternative approaches, but I don’t know if that resonates with you.

Jae Park (20:03):

I mean, I think when it relapses it’s always very difficult. I think whether it’s relapsing of the chemotherapy, blin, ina, transplant and the CAR-T certainty, as CAR-T is moving earlier lines of a therapy, we may have a little bit more tools later on to use it to get them into remission again. But I think that one of the data that came out of the T-cell wearable data and then hopefully we will get more data is the MRD monitoring or the deep level monitoring after the CAR-T cell infusion is one of probably the more important factors to monitor these patients. So we are already doing that in the front line setting, all of us do that for pediatric adult patients with an ALL, the data also appears to be clear for the MRD and not just for CAR-T for any others there as well.

(20:42):

So high burden patients, I certainly do worry about relapse and those are the patients that I will be thinking about else other than CAR-T, often being allogeneic transplant for those patients. But if they’re MRD positive by NGS and the 1 million kind of cell sensitivity at day 30 or even month three even before morphologic relapse, we already know that patients are destined to relapse. So before they lead into morphologic relapse that hopefully we have a better tools than transplant in the future. But for right now, that’s probably one of the better tools that we do have, especially for transplant naive patients. So the monitoring appears to be the key, I think with a deep sensitivity monitoring, I think it’s probably one of the better way to predict them.

Bijal Shah (21:20):

I don’t have anything smart to add. I think it’s still an undefined space.

Noelle Frey (21:24):

Yes, a lot of work to be done, I think. And there’s a lot of trials, the only thing I would add is there’s a lot of trials, which we didn’t get into today because of time, but going after more than one antigen. So the goal there would be to minimize the risk of relapse due to antigen escape. And while the ideas are there, I think we have yet to see kind of that long-term impact. But maybe in the next couple of years we’ll be able to do that. Well, thank all of you for joining us today and thanks you listeners.

Understanding the CAR-T therapy process

Dr. David Maloney (00:05):

All right. Good afternoon. I’m Dr. David Maloney, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. I’m the medical director of the cellular immunotherapy program there.

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (00:16):

And I’m Dr. Sarah Nikiforow. I work at Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. And I’m part of our allogeneic stem cell transplant program. But I’m also technical director of our immune effector cell program, which oversees both commercial and investigational CAR therapies.

Dr. David Maloney (00:33):

So, I think what we would like to try to do today was to walk through the CAR-T cell process and to try to ensure a few things. Number one: how do we get more patients to get this lifesaving therapy and to get it in a timely fashion, where it’s actually going to be expected to work better? Because there are some things we can do that will increase the chance of success and decrease the risk to the patients in terms of safety. So, we’ll try to walk through that process. I guess, the first thing we could talk about is referrals. I mean, what is important in getting referrals to the trials?

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (01:12):

And, David, I think we were going to chat about the, mainly focusing on the hematologic malignancies and commercial CAR-T cells, right?

Dr. David Maloney (01:18):

Yeah.

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (01:19):

Because some of this will be generalizable to solid tumors and to trial patients, but I think it’s the vast majority of patients that we are trying to capture, right now, are going to be the heme malignancy patients on the commercial therapies. And so, you have probably set up a similar pattern, but, as a large academic center that also has a stem cell transplant program, right?

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (01:42):

We have a referral basin already of groups that, with leukemia, lymphoma and myeloma patients, already refer in to specialized hospitals for autologous or allogeneic transplant processes. So, I think we’ve tried to leverage some of those existing relationships, but also emphasize it’s somewhat different than an allogeneic transplant.

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (02:04):

When patients are referred in for consideration of CAR-T cell therapy, this is something that we would bring folks in, evaluate their eligibility, but then, after we get them through the therapy, that we’ll describe as we go forward, we would actually hand them back. So, it really is a partnership, over time.

Dr. David Maloney (02:25):

No. I think that’s exactly true, but I think the key point here is that, there’s only a few centers that are capable of doing this. I mean, there are hundreds, I guess, now, in the United States, but it’s not something that each community center is likely to have available. It’s a complex treatment. It requires access to expert care, that can manage the patients through the expected toxicities. It has to be done at a major academic center that has ICU care available to the patient. So, as you said, most people are referred into programs that are generally been, at least traditionally been through the bone marrow transplant programs, because that’s where that expertise and that referral pattern happens.

Dr. David Maloney (03:13):

And I think that, so it starts with, I think, recognition of who’s eligible for this treatment. And the key thing there is that these… Well, the CAR-T cells, for example, for aggressive lymphoma, used to only be offered to relapsed and refractory patients. And, now, they are standard of care for first relapse, large cell.

Dr. David Maloney (03:35):

And so, time is of the essence. In fact, if you can get the patient referred to a CAR-T cell center before they even need second-line chemotherapy, or as soon as you know that they’re primary refractory, then they’re eligible, potentially, for CAR-T cells in the second-line. I think that that’s key, because we do know from the ZUMA-1 data, original clinical trial data, that the patients with the lowest tumor burden actually had the best outcome. They had the highest cure rate, the highest CR rate. And they also had, conversely, the lowest toxicity.

Dr. David Maloney (04:13):

So, if you were in the lowest quartile of tumor burden, you had a nearly 70% remission rate, at a year and you also had almost minimal toxicity in terms of only Grade 1 and 2 CRS. So, if we could get patients referred earlier, the results are better, just by going into the second-line, and also, if you can get patients before they need more treatment, the results are better.

Dr. David Maloney (04:38):

So, my plea is, from community oncologists, is to get this to patients, before they cycle through the next three treatment options. Those options will still be available if they fail CAR-T cells, but the best chance to cure your patient is to do it as soon as possible, as soon as they’re eligible, which in large cell is like second-line therapy.

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (04:57):

Yeah. So, David, what you’re referring to is key. And the landscape is changing so quickly. And we’re even expecting approvals, I believe, in May of 2024, of CAR-T cells against BCMA, in earlier lines of therapy for myeloma as well. So, I think the general premise that the earlier you refer patients to cell therapy centers, to at least get evaluated, is better, in both lymphoma and in myeloma.

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (05:25):

And for those in the audience who are not aware, there have been randomized trials, you were speaking of second-line, but there have been randomized trials in all of the CD19 CAR-T cell therapies, randomizing patients in their first relapse, between standard of care, which is chemo and autologous stem cell transplant and CD19 CAR-T cells and two of those were positive, way in favor of the CAR-T cells, so I think that’s a practice paradigm shift that not everyone might be aware of.

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (05:54):

But, yes, refer early. And we’ve even… I think it was what? Last month, CD19 CAR-T cells were approved for relapsed/refractory CLL, so not just the phase of therapy that you can target, but also the diseases that are amenable to CAR-T cells are constantly increasing.

Dr. David Maloney (06:12):

Yeah. So, we now have CAR-T cells approved for large cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, the indolent lymphomas, follicular and marginal zone, and, now, CLL. And that’s very exciting. And, obviously, the high-grade malignancies as well.

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (06:27):

Yep.

Dr. David Maloney (06:28):

So, what process do you guys use at your center to get patients coming in the doors from, say, an outside site? Do they contact just the hem group, or do you have a process to get them into your system?

Dr. Sarah Nikiforow (06:40):